Tuesday last week, with the help, support, and expertise of friends and an experienced mountaineering guide, I summited Mount Hood for my first time, and activated Mount Hood for its first time in SOTA. The climb began under a crystal clear starry sky around 00:37 on Tuesday, 11 June 2013, heading up the snowcat-groomed climber’s trail from Wy'East Day Lodge at Timberline Lodge. At midnight, I had met my guide, Rodney Sofich, at the Climber's Register just inside the day lodge to discuss what I was about to undertake.

The Buildup

"You may have hired me for reasons you are not fully aware of," Rodney warned me. Many climbers have died or injured themselves on Mount Hood when they decided to press on to achieve their goal even when proper risk management indicated it was time to turn back. Even seasoned climbers in top physical condition turn back if the fickle mountain weather becomes too dangerous, or the expedition isn't able to move quickly enough to reach the summit and then descend out of avalanche territory before the warming daylight creates hazardous conditions at higher elevation. Rodney made it clear he might have to make an unpopular executive decision, in order to manage our risks conservatively, and he apologized in advance if he needed to turn us around for any safety reasons before reaching the summit. Which means I found exactly the right guide!

We left the overnight parking lot outside the Wy'East Day Lodge sometime between 12:30 a.m. and 12:45 a.m., and for the first two or so hours we walked in the dark, looking down in the circles of our headlamp beams at the groomed but choppy snow of the climber's trail that skirts the east edge of the Magic Mile and Palmer ski slopes above Timberline Lodge. We wore plastic mountaineering boots with insulated inner boots, insulated long underwear, wind pants and jacket, gloves, and warm, snug-fitting insulated hats that blocked the wind and covered the ears. In my pack were two liters of gatorade and a liter of water (with wide-mouth bottles that allow easier picking with your ice axe if your drinks freeze!), a PayDay candy bar, a Snickers, several Gu packets, a couple Pro Bars, a couple Honey Stingers, which are like Gu but are honey-based, and a Butterfinger. One's appetite and thirst can fade at high altitude, but eating, drinking, and sleeping well are exactly what help the body to adjust to higher altitudes and help prevent altitude sickness. The hike up Hood is so strenuous, too, that you really need the calories up there to keep warm and to be able to keep going—you can't stop for hours on the mountain to rest. So for a half day, I lived off of essentially candy, because I needed to know I was going to want to eat what I brought.

A week before, I had completed a nine-day solo backpacking trip on the Appalachian Trail with a sixty pound pack (I was carrying food for the entire trip, having planned for no resupplies), including a traversal of the infamous Roller Coaster section of trail south of Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. However, even with our comparatively featherweight packs, I found that walking on snow, walking in mountaineering boots, walking at elevation, walking in the cold, and in fact walking at night are all each strenuous in their own way. My body’s rhythm was thrown off as I'd slept only an hour or so the night before, finding myself nervously anticipating the climb while laying in bed in Government Camp trying to get some shuteye after an enormous dinner. In fact, the first two or three hours of the climb, which had the lowest incline, arguably the easiest snow quality for walking, and during which my legs were the freshest, was probably the part of the whole expedition when I was most nervous. I didn't know what was ahead. The mountain, if at all visible, was only a dark shadow blocking the stars ahead and above us. And the images of the final approaches to the summit that I contemplated as we walked up the climber's trail seemed impossibly steep, exposed, and without anything to keep us from falling, let alone actually to climb up.

Mountaintop Terrain and New Snacks

Sometime around 3:00 a.m. we made it to another path that contours east from the top of the Palmer ski lift, and the uphill side of this path is dug into the snow, providing a good windbreak, and it was here that we walked up and sat down not far from another group that had set out before us. This was our first snack break, as we had made good time up the climber's trail, and since I didn't really have an appetite Rodney recommended one of the gel packets. I think I tried a Honey Stinger, my first, and while it started off fine I found myself having the same sort of headache that I get if I have a spoonful of honey by itself. (Later in the trip I tried a Gu, and it hit the spot.)

Even with the wind break from the wall behind us, we got cold quickly, and after putting on crampons we climbed up the wall (everything is easier with crampons!) and continued our night hike, now on slightly steeper terrain, often following frozen footprints from the previous days' climbers, and now going diagonally up and to the left, toward Crater Rock.

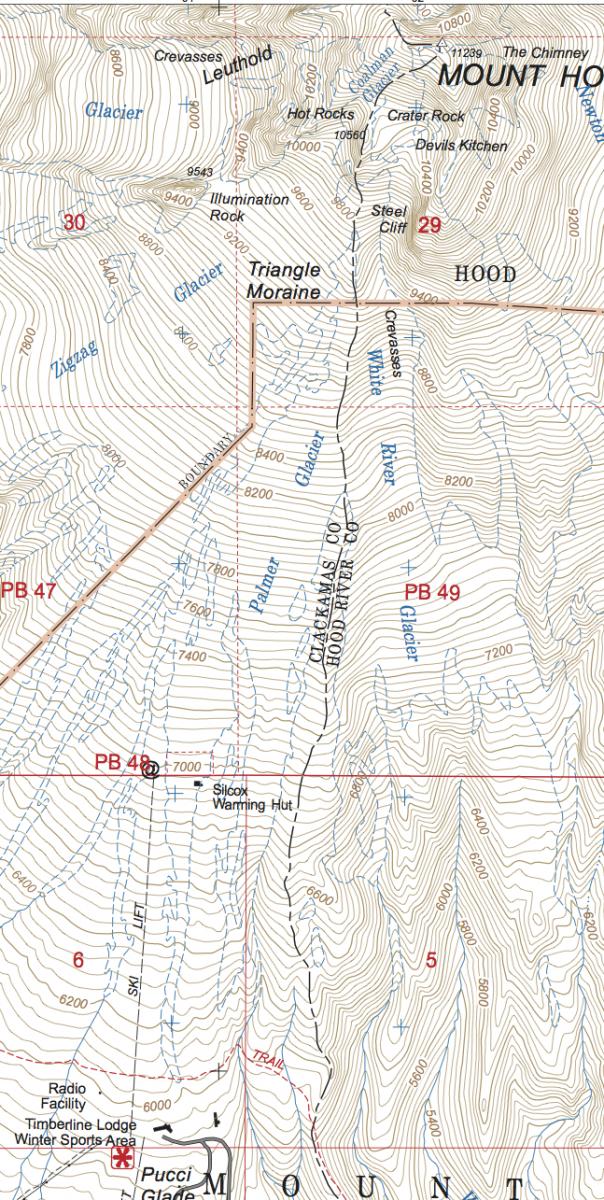

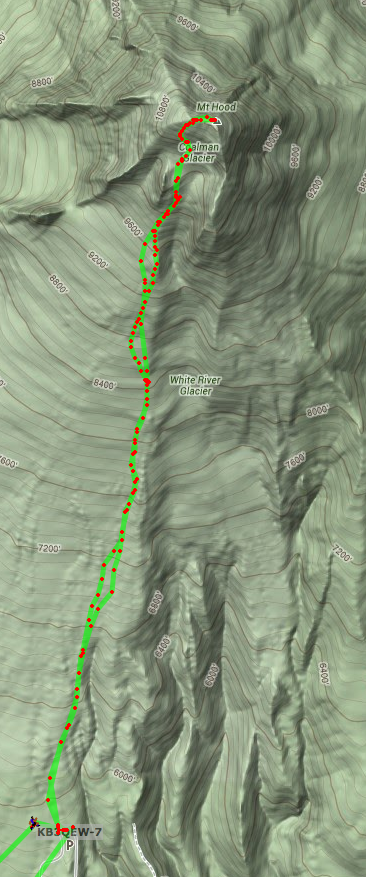

Here’s a detail of Forest Service topographic map number 451512137, “Mount Hood South” (left), and a screenshot (right) of the APRS.fi website showing my tracks up and down the mountain:

(Down at the bottom is the Timberline Lodge and Wy’East Day Lodge and parking areas, and up near the top is the summit.)

The top of Mount Hood, looking at it from the south, is essentially a semi-circle ring-like ridge that opens to the south, with Crater Rock sticking up at its mouth. On either side of Crater Rock, sort of behind it and in the valley area inside the C-shaped ridge, are fumaroles that smell like acrid hard boiled eggs. We stopped for a short, five-minute break below Crater Rock, and then took a longer, fifteen-minute break on a plateau higher up, just east of Crater Rock. Here we put on mountaineering harnesses and helmets, and Rodney readied his rope. The sulfur smell was gentle at first, but every once in a while we'd get a strong whiff of it coming over on the breeze! We were relatively sheltered here from the wind, too. At this point, the group that we had caught up to on the road by the top of Palmer was now catching up to us, making its way up to the plateau as we were finishing preparations to continue on. Before leaving, we got out our ice axes, which we used like walking sticks to steady ourselves, and Rodney stuck his hiking pole into the snow and left it there to pick up on our return down the mountain.

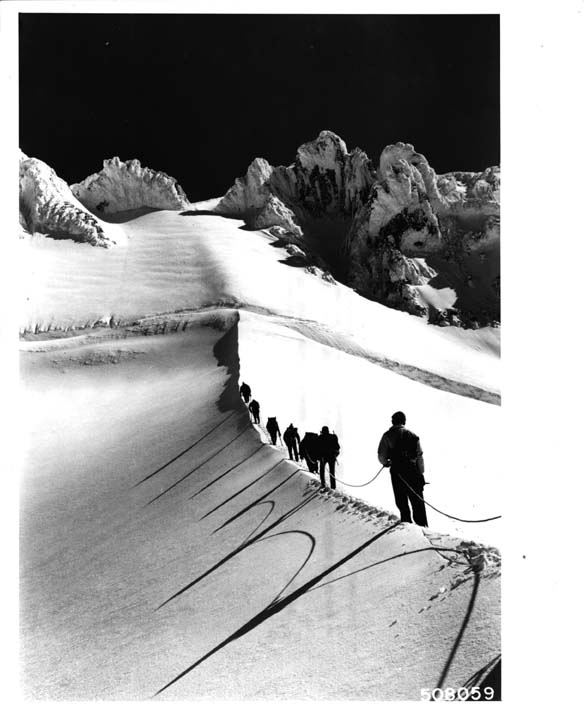

The Hogsback is the name of a smaller ridge line of snow that runs from the back (north) of Crater Rock through the middle of the valley and up the middle of the back of the C. To either side of the Hogsback are the fumaroles, and crossing the hogsback about half or two thirds of the way up is the Bergschrund. Here are two photographs taken behind (north of) Crater Rock, and looking up and north to the center of the C-shaped ridge that forms the top of the mountain:

(Both photos taken by the Forest Service, available at http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mt.HoodJune20.jpg and http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Coalman_Glacier_usfs_508059.jpg.)

A bergschrund is a special kind of crevasse, and the name denotes one that forms in particular where the top of a glacier pulls away from the headwall at the top of the valley. At this time in the year, Mount Hood's bergschrund across the Hogsback is now longer covered by snow bridges, and is a visible cleft in the snowy ridge line, about four to ten feet wide, maybe sixty to eight feet wide, and about as deep. Having roped up together before ascending from the plateau to the Hogsback, and then walking along the ridge of the Hogsback, we then got up to below the bergschrund, where we started contouring to the left, onto Coalman Glacier.

There are many different final "approaches" to the summit, and even the subset of those on the "south side" are still numerous. If one skirts the bergschrund and continues along the Hogsback above it, for example, one reaches the "Pearly Gates," which itself is a pair of routes around a rock that rises in the middle of the trail, visible in the two photos above.

Recently, however, the Old Chute, which is a snowy opening in the rocky outcroppings above Coalman Glacier, west of the Pearly Gates, is apparently the approach used by many expeditions. The snow, terrain, and rock changes from year to year but also from week to week as the seasons change, so the accessibility, exposure, and risk of snow and rock fall of any given approach also changes from year to year and from week to week.

Ascending the Headwall

When we were roughly below the Old Chute, we started to climb straight up the wall of the mountain, essentially a very steep, snowy, crusty staircase. In fact, the conditions were ideal: steps had been made into the then-mushy snow on the down climbs of previous expeditions during warmer temperatures later in the day on previous days, and had hardened overnight, and we simply walked up these steps. But they are big steps, and we'd already climbed about 4,000 feet in elevation over only a couple miles at this point, my legs felt like they had given almost all they could give without another break, and the thin air of course makes one feel more out of shape. I found that if I thought of reaching the top of the Old Chute and of the short walk over to the summit proper, I was overwhelmed, and could not imagine making it, even though horizontally we were probably less than a quarter mile from our destination. However, I just kept telling myself, "well, this step, I can take this step. This is working. Now, it's time for this step. I am taking this step. I can take this step too." One by one. My pace had slowed down on the way from the path by Palmer up to Crater Rock, and Rodney noticed. Now, I was even slower. About this time, John N7AAM on Council Crest snapped this photo of his mobile unit's readout of my APRS beacon:

And then all of the sudden we were on top!

A Sea of Clouds

Rodney took this photo, which looks west over the lower-elevation cloud cover, with some rock features at the top of the mountain in the near background. We're a couple steps to the east of the Old Chute (which I believe is not visible in this photograph), and still a couple minutes' walk from the summit proper. (Walking goes slow and steady at high elevation with wind and precipitous falls all around!!!) By the way, that's the antenna of the VX-8GR sticking out of the zipper from the top compartment in my pack behind my helmet.

As we were climbing, it had gotten lighter, and the sun had begun creeping over the top of the mountain to light up the inside of the valley walls a bit, and even touch the thick, cottony cloud layer that had formed around 8,000 feet and shrouded everything below it, looking like one big sea of cottony fluff that extended to the horizon. But where we were, at 11,000 some odd feet, was perfectly clear, and the orange sun cast everything in a beautiful light.

Walking on Top of the World

It was windy, but not too windy, and I made every step count: now was not the time to trip! We had just come around a rocky mound on top of the mountain and into the sun when I heard Taylor’s voice on the radio, identifying K7TAY, and Rodney asked if I was going to respond! But I saw the official summit just ten or twenty yards onward, and even though we were less than ten vertical feet from the summit I couldn't resist the opportunity to do the communications from the summit itself (not to mention to be on the actual summit in the first place)! I asked Rodney if it would be OK, and he said it would, as long as the chasers could wait two minutes :)

There was a sort of saddle between us an the summit, and while walking across this saddle, slowly, I could look down to the right and, I think, if I remember correctly, see Crater Rock at the bottom of the Hogsback, but I don't remember for sure. It looked like a long fall, but nothing compared to the shear open space to the left of us. The ground (hard snow) rose at a slight angle to our left, stopped abruptly, and beyond were only clouds. I’d read that, on top of the summit, a fall to one side would be a couple hundred feet, while a fall to the other would be several thousand.

Halfway across the saddle, I asked Rodney if it would be ok to lie down and slide up to the edge and look over. He looked at the snowpack and pointed to a spot three or four feet in from the edge, and said “here,” so I lay down and only crawled up that far. We looked down and could see Elliot glacier below, Mount Rainier, Mount Adams to its right, and to the left Mount Saint Helens, whose top barely rose above the clouds, flat and low compared to the others. But while Mount Saint Helens was surrounded by clouds in the distance, directly below us on the east/northeast side of the mountain it was clear, and we could see down into the valleys.

After a minute I got up and we continued to the summit. We took off our packs, and I got out the radio. While walking over to the summit, I’d heard Taylor and the others talking on the Mount Hood Repeater frequency, which I'd been monitoring during the entire ascent, so I tried calling on that frequency several times, first for K7TAY directly, then “CQ CQ anybody anywhere,” but got no replies. “Bummer!” Rodney said. I was afraid something might be wrong with the radio, like perhaps the keypad had become unlocked in my pack and some settings changed. I had some trouble switching between the Mount Hood repeater and national simplex frequencies stored in the first two memory slots, so I turned the unit off, back on, and then was able to switch back to the memory slot that stored national simplex, and I made the call, and everyone came through!

Loud and Clear

Rodney took this photo too, which also looks west, showing the shadow of the mountain, a sundog (rainbow-like ring around the tip of the shadow), some of the snow-covered features on the top of the mountain, and, of course, QSOs in progress. As you can see, the wind is strong enough to bend over the antenna about ninety degrees! I split the difference by tilting the radio into the wind, but I suspect this may not have helped much.

It was such a joy to talk to folks, and everyone in the planned party came through loud and clear: N7HQR, N7AAM, K7TAY, AE7LD. On all contacts I received a strong signal that was completely readable, and I think most of my transmissions were received that way, too. We even had someone from about 20 miles south of Salem who must have been monitoring who responded right when Taylor was asking “how is it up there?” I wanted to pick them up and make sure they got a chance to connect, so I called back and we made the contact. It was too cold and windy and I had too few hands to log, so all I was able to catch was a W7 and a WV. After that, I don’t think I heard anybody for a while, and it was time to get going on our descent, so I signed off, thanking everyone. On my final I indicated that I’d monitor but would not be able to respond or transmit, because we were going to start down climbing. As Rodney and I crossed back over the saddle from the summit I heard a KF station call in and thought drat! It would have been great to make contact with them, too, and give them a piece of the Mount Hood pie this morning! But we were on the move and it was time to get down from the mountain before the sun started to warm things up. Oh, yes, and before any other groups got to the top wanting a turn at the summit: we'd made it up there before anyone else that morning, even the groups that had set out before us! About five hours from the parking lot up to the top...

Down, down, down…

And about three and a half hours of down climbing and hiking were ahead of us, but this time in daylight! The climb down the Old Chute started out very difficult, but fun: side stepping (one-two-three: downhill foot, uphill foot, ice axe [which is always on the uphill side]). However, it felt difficult to pick the right spot to put my feet, even though there were really good boot print stair cases. At some point early in our descent, Rodney instructed me to face forward—downhill—and walk down it like a regular staircase! Suddenly, facing the whole world in front of me (Crater Rock and the Hogsback to the left, clouds and country out straight ahead) I felt more comfortable. Somehow Rodney knew that this position/stance would allow me to feel more confident during the down climb, and to get into more of a flow. It seems like a less conservative way to down climb (versus side stepping), but the snowpack and boot print steps were in good condition. Down climbing in that fashion was like meeting the mountain all over again! Just 6 hours earlier, we’d been hiking up from Timberline Lodge on the climber's trail in the dark, with all the stars above us, looking at the snow and placing our steps in the light from our headlamps, feeling the rhythm of a good pace come and go every 15 minutes or so, with me wondering silently how much I had bitten off, and how and whether I’d be able to keep up the necessary pace, whether I’d reach the edge of my comfort zone before reaching the top.

Rodney snapped this pic of the Bergschrund from the side (looking east) as we climbed back down Coalman glacier from the Old Chute before contouring over to the Hogsback again; it’s actually probably four to six feet wide in this picture, probably about forty feet end to end, and maybe sixty to eighty feet deep:

When we made it back to the base of the Hogsback, we stopped briefly to unrope, grab a snack and a drink, and headed down again. I hadn't eaten anything while on the summit, having spent the entire time we had up there (about 20 minutes) operating, and was almost shaky from low blood sugar by the time we got to the low end of the Hogsback. After fueling up, we continued down, again stopping at the trail leading along the contour of the mountain to the top of Palmer lift to take off our crampons and harnesses. We met two folks who were headed up (it must have been about seven or eight in the morning now), who asked which route is best to get to the summit, and I tried to tell them they'd better turn back soon and try again another day—way too late of a start to make it to the summit and still be able to descend relatively safely! They'd have a minimum of four hours ahead of them inside acute rockfall and avalanche territory, a four hours stretched over the middle of the day when snow would start to soften, even melt, and things could shift... they said they'd driven a long way in order to attempt to summit Mount Hood, but they obviously hadn't done their homework and neither of them seemed very experienced or trained.

Reflecting on my own

Rodney went on ahead after the trail at the top of Palmer, and let me take my time hiking the last two miles downhill back to Timberline Lodge. By this point, my legs felt like jello, my knees ached, and I was in awe of having a totally new relationship with the top of Mount Hood: I'd actually walked all the way up there! I couldn't believe how fast the summit, the Hogsback, and Crater Rock were receding behind and above me. I only took one more break for a candy bar and some gatorade on the way back to the parking lot after taking off crampons at Palmer, but I did stop and turn around several times to soak it in, to look up at the cliffs, and, slowly, to watch the mountain top be swept up in the "low" hanging cloud cover we'd looked down on from the summit. Here’s a picture I took of myself trying to eat a frozen PayDay candy bar, with my new playground in the background:

When I got back to the overnight parking lot at the Wy'East Day Lodge, it was 9:20 a.m., and we'd just summited and returned in about eight hours and forty minutes! Pretty zippy, apparently. I'd like to be in better shape next time, so I can be more comfortable, but with the very, very favorable conditions we had, my fitness level was quite adequate.

After shaking Rodney's hand something fierce and thanking him from the bottom of my heart, I hobbled over to Timberline Lodge and plopped down at a table looking south out a big window.

On APRS.fi, I found one of my track points (timestamp 2013-06-11 06:03:09) at an altitude of 11,250 feet!!!

The Team

All in all, we were:

Rodney Sofich - Lead Guide at Timberline Mountain Guides

N7HQR at 5:56 a.m. - Daron on Mt. Hebo

N7AAM at 5:56 a.m. - John on Council Crest

K7TAY at 5:56 a.m. - Taylor on Sylvan Hill

AE7LD at 5:57 a.m. - Joe with Taylor on Sylvan Hill

Later we were able to confirm with Mikael W7WVC in Scio, OR, that we'd made contact at 5:58 a.m.

Dan KK7DS and Taylor K7TAY helped a lot by lending gear, offering guidance, and coordinating the chasers!

Next Time

On the way up, I'd thought I probably wouldn't summit Hood again—but after summiting and on the way down, I realized I definitely want to go up there again and learn more about mountaineering, get some avalanche training, and become more accustomed to traveling on glaciated terrain. It is so beautiful up there.

Climbing Mount Hood was a lot of fun, but I never would have attempted it without first having attended a Snow Skills clinic and a crevasse rescue training (Rodney taught these) earlier in the spring. I also would not have attempted it without the leadership of someone as experienced as Rodney. Someday I hope to have the skills, and the miles and contour lines under my crampons, to attempt Hood on my own. But this trip was excellent, and because I also take a conservative approach to risk management in the outdoors I thought Rodney’s guiding style was a very good fit for what I was looking for. Rodney does his job excellently and I would recommend him to anyone looking for an experienced mountaineering guide.